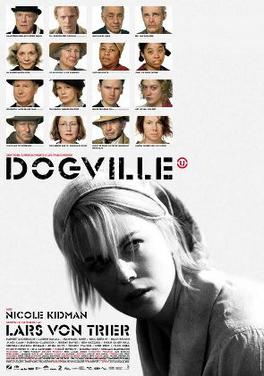

Today I was watching von Trier's own film from the same time period Dogville (von Trier, 2003), and it struck me that von Trier's entire English language career (his Danish language films are another story) has been a Five Obstructions-style series of remakes. Von Trier keeps remaking the same movie a female Christ-figure -- a pure-hearted woman who suffers unjust torments in order to save someone she selflessly loves. In Breaking the Waves, von Trier challenged himself to shoot the film in a hyper-realistic hand-held camera style; in Dancer in the Dark he remade the story as a musical; and in Dogville he remade the film on a single sound stage without any sets in the manner of Thornton Wilder's Our Town or a Bertolt Brecht play.

Today I was watching von Trier's own film from the same time period Dogville (von Trier, 2003), and it struck me that von Trier's entire English language career (his Danish language films are another story) has been a Five Obstructions-style series of remakes. Von Trier keeps remaking the same movie a female Christ-figure -- a pure-hearted woman who suffers unjust torments in order to save someone she selflessly loves. In Breaking the Waves, von Trier challenged himself to shoot the film in a hyper-realistic hand-held camera style; in Dancer in the Dark he remade the story as a musical; and in Dogville he remade the film on a single sound stage without any sets in the manner of Thornton Wilder's Our Town or a Bertolt Brecht play.The strange thing is that Dogville ends quite differently than the previous films it is remaking. In the earlier films, the suffering woman is eventually killed but brings a kind of redemption through her death. These are clearly New Testament sort of stories. At first Dogville seems to be following the same narrative, but in its last ten minutes the story suddenly turns Old Testament: a God-like gangster shows up and convinces the film's Christ-figure to choose judgment over forgiveness. I'm not sure what to make of this. Is von Trier repudiating the earlier films? Or is he merely showing us another aspect of the infinitely complex truth?

At one point, the philosopher-novelist character says he is writing a story based on the events of the film. When he adds that he hasn't come up with a good name for the town yet, the heroine asks him why he doesn't just call it Dogville. He replies: "It wouldn't work. It's got to be universal." Well, if the movie we're watching is called Dogville, does that mean it isn't (and isn't intended to be) universal? So perhaps the point of the film is not to reject forgiveness and mercy entirely but to remind us that grace is not the whole story: there is judgment and justice, too. Rather than read Dogville as a critique of the Gospel narratives, perhaps we should read it as a retelling of the Sodom and Gomorah narrative: God sends an angel to the town but the people rape her and so God destroys the town. This isn't the prettiest story in the Bible, but it is still in there and must be reckoned with.

Starting from this reading it is tempting to see the film as von Trier's reaction to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. (This was von Trier's first film made after 9/11.) Perhaps, like Jeremiah Wright and Jerry Fallwell, von Trier is interpreting the terrorist attacks as God's judgment on the United States. Especially in light of the closing credits which plays David Bowie's "Young Americans" over images of American crime and poverty, combined with the film's Prologue about the philosopher's attempt to teach the town a lesson about their inability to receive good gifts, von Trier seems to be saying that God has given the U.S. grace upon grace but we have not provided God's gifts with a hospitable place in which to live and bear fruit. And if we persist in our inhospitality we will face God's wrath.

Fortunately this is only one aspect of the infinitely complex truth. Instead of following the townspeople of Dogville, we might instead follow the selfless heroines of Breaking the Waves and Dancer in the Dark. We might choose to take the world's suffering on ourselves and to transform it into an opportunity for love.