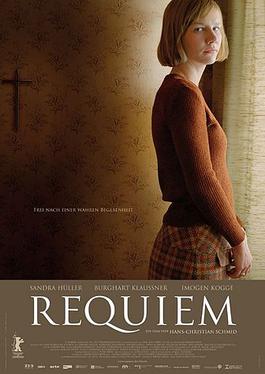

Recently there were two movies made based on the life of Anneliese Michel, a German college student from the 1970s who claimed to be possessed by a demon. My fellow Biola University alum Scott Derrickson updated the story to 2000s era America in his horror genre film The Exorcism of Emily Rose (Derrickson, 2005). German filmmaker Hans-Christian Schmid made a more straightforward dramatic biography of Anneliese in Requiem (Schmid, 2006). The result was a far more subtle and interesting film. (Sorry, Scott!)

Recently there were two movies made based on the life of Anneliese Michel, a German college student from the 1970s who claimed to be possessed by a demon. My fellow Biola University alum Scott Derrickson updated the story to 2000s era America in his horror genre film The Exorcism of Emily Rose (Derrickson, 2005). German filmmaker Hans-Christian Schmid made a more straightforward dramatic biography of Anneliese in Requiem (Schmid, 2006). The result was a far more subtle and interesting film. (Sorry, Scott!)Derrickson’s movie is set up as a courtroom investigation which asks us to decide whether we think Emily is really possessed or not. Requiem is not interested in that question. In fact the film seems to assume that the girl (in this version called Michaela) is not really possessed. Indeed, it seems to assume that she knows she’s not really possessed. Instead, the film asks us why, if she knows she is simply sick and not really possessed, she would go along with her mother and priest’s exorcism scheme? The answer the film suggests is that she wants to recontextualize the meaning of her suffering. If she is simply sick, then her suffering is random and meaningless; but if she is possessed, then she is a martyr.

Once Michaela interprets her own life through the lens of St. Catherine, her own favorite saint, she is able to accept her suffering with peace. Prior to this, she is “ashamed” of her illness, and wants to be a normal kid. The “voices” she hears are her mother’s voices telling her she is a “slut” and that she is not capable of going to college. But when she first attempts to interpret these feelings as demonic possession, her liberal priest tells her that the Devil is only a symbol and recommends she seek medical attention. Then, when, the stress of school almost prevents Michaela from completing the first semester, and her boyfriend wonders if maybe college is not the best place for her, she realizes her mother will be proven right. She begins to give herself over to her symptoms in order to press the possession interpretation, and to show that it is not her weakness that is preventing her success but the Devil. Hence the movie suggests one use of the symbolism of evil is to allow us to create a meaningful narrative out of our suffering.

Once Michaela interprets her own life through the lens of St. Catherine, her own favorite saint, she is able to accept her suffering with peace. Prior to this, she is “ashamed” of her illness, and wants to be a normal kid. The “voices” she hears are her mother’s voices telling her she is a “slut” and that she is not capable of going to college. But when she first attempts to interpret these feelings as demonic possession, her liberal priest tells her that the Devil is only a symbol and recommends she seek medical attention. Then, when, the stress of school almost prevents Michaela from completing the first semester, and her boyfriend wonders if maybe college is not the best place for her, she realizes her mother will be proven right. She begins to give herself over to her symptoms in order to press the possession interpretation, and to show that it is not her weakness that is preventing her success but the Devil. Hence the movie suggests one use of the symbolism of evil is to allow us to create a meaningful narrative out of our suffering.Note that on this interpretation the film is not necessarily arguing the liberal point that the Devil is just a symbol. The film’s view that Michaela is using the Devil as a symbol is compatible with the conservative Christian view that the Devil is also literally real and can possess other people. More likely, however, the film is making a post-liberal point: it is the Devil oppressing Michaela – in the form of her mother’s criticism (and to a lesser degree in the form of her physical handicap). In other words the Devil is a symbol, but the Devil is not just a symbol, because symbols have their own kind of reality and so no symbol is just a symbol.

Question: I haven't read Paul Ricoeur's The Symbolism of Evil, but from what I understand my reading of Requiem is similar to the kind of thing Ricoeur is doing in that book. Does anybody out there have any insight on this?

No comments:

Post a Comment